Large projects are always daunting. Many of us understand the stress of reading a long-winded and complicated prompt and turning to a blinking cursor on an empty Word document. Many feel that stress helps them start working, but a lot of those same people will admit to putting off work to avoid that stress. This is what we call avoidance.

While it may seem counter-intuitive, a lot of people see stress as a demotivator. The fear of negative evaluation from your professor and peers can be quite daunting. I personally feel that this is what motivates most of my procrastination. I fear the pressure of a bad grade, so I put an assignment off till a “better” time arrives. Waiting almost never works in your favor; time is too valuable a resource. The best way to get started and to keep working is to make a big project less daunting.

The simplest way to make a big task manageable is to divvy it up into smaller tasks. A paper can be divided up into brainstorming, outlining, drafting and editing. Studying for a big test can be split into rereading, highlighting and practice problems. The point is to divide up a large task so that you can have regular breaks in between periods of work and so that you can approach the same material in a variety of ways.

Why would we want to do this? Approaching the same material in a different number of ways can stave off the boredom of monotony and it can help your memory. When studying for a test you can

- Read the material out loud.

- Rewrite your lecture notes.

- Write a summary of each chapter or topic.

- Discuss the subject with others, be they a classmate, a friend, or the professor.

Regular breaks are great to keep up motivation and avoid exhaustion. The human mind needs regular rest to work effectively and sleep is essential to our memory. For breaks you should

- Work for blocks of 40-50 minutes and break for 10-20 minutes.

- Reward yourself during your breaks: get a bite to eat or call up your friends and family.

- Make sure to get up and move during your breaks, the human body is not designed to sit for hours at a time!

There are many resources out there available that can help with divvying up you work. It is completely within your means to find strategies that work for you. I highly recommend trying to do so, as any one tool isn’t perfect, but here are some of the tools that I’ve become acquainted with.

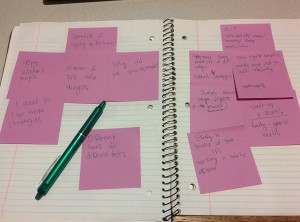

Post – its and Google Keep

Post – it notes are wildly helpful. They can be used for quick notes, bookmarks, reminders and many other things. They are great for writing down short ideas or summaries that can be later organized into a larger narrative. They’re also very portable and can be taken anywhere.

Post – it notes are wildly helpful. They can be used for quick notes, bookmarks, reminders and many other things. They are great for writing down short ideas or summaries that can be later organized into a larger narrative. They’re also very portable and can be taken anywhere.

Google Keep is an online alternative for Post – it notes. Google is used extensively by the current generation and this trend does not seem to be waning in any way. Google offers a suite of options and deserves as much mention for its price tag (free!) as its utility. I should also mention that Google’s entire “utility suite” is available and set up as soon as you activate your Google account. The benefits of electronic “sticky notes” are that you can later edit the color of your notes and set reminders by email or by phone (if you have Google Now installed). Visual learners may readily benefit from this as they can color code ideas after the fact, without having to categorize ideas before they even write anything. Reminders are invaluable for me, as they allow me to play both the role of a reluctant student and that of a nagging parental figure.

Google Keep is an online alternative for Post – it notes. Google is used extensively by the current generation and this trend does not seem to be waning in any way. Google offers a suite of options and deserves as much mention for its price tag (free!) as its utility. I should also mention that Google’s entire “utility suite” is available and set up as soon as you activate your Google account. The benefits of electronic “sticky notes” are that you can later edit the color of your notes and set reminders by email or by phone (if you have Google Now installed). Visual learners may readily benefit from this as they can color code ideas after the fact, without having to categorize ideas before they even write anything. Reminders are invaluable for me, as they allow me to play both the role of a reluctant student and that of a nagging parental figure.

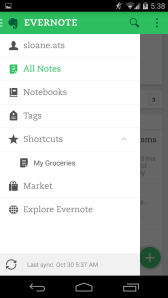

Notebooks and Evernote

Notebooks are the staple of any student. Every student owns at least two or more. They make perfect calendars and task books, but they are mostly used for note taking. There are many ways to “more effectively” use a notebook, but one strategy has caught my eye and seems simple enough to actually use. It’s called Bullet Journal. This link will take you to a page that details the process and offers a quick video tutorial. Basically at the start of each month you create an index for your tasks, a calendar that gives a quick summary for each day and then a more detailed day to day list of the assignments or tasks to be done. This method is especially handy for students as they are bound to have an extra journal lying around, or they have a journal with a few extra pages, which is all this method really needs.

Evernote is an online not taking suite. You can create a free account that allows you to sync between a web client, a PC application and a mobile app. Each note you create is searchable and you can divide your entries into “Notebooks” and further categorize each entry with a searchable “Tag”. Like Google Keep, you can set reminders for your different notes so that you will receive messages at a later date.

Evernote is an online not taking suite. You can create a free account that allows you to sync between a web client, a PC application and a mobile app. Each note you create is searchable and you can divide your entries into “Notebooks” and further categorize each entry with a searchable “Tag”. Like Google Keep, you can set reminders for your different notes so that you will receive messages at a later date.

Calendars and Google Tasks and Calendar

If you opt to purchase a dedicated calendar or planner, there are many options out there. The only criteria for a purchase is that you know you will at least try to use it. Also if you decide to spring for a monthly calendar, make sure that it is large enough for you to write down what you need to! Monthly calendars are great for writing a quick summary of the tasks you need to get done and to see which weeks will be your busiest. However, even if you do choose a large calendar, it will not have room enough for a detailed daily task list. A planner would be necessary for detailed lists, and is encouraged if you do not already have a system in place and you have difficulty remembering the fine details (Who am I meeting? Was it room 306 or 360? Did I need to bring anything with me?). Also planners are quite helpful because of their portability, you usually can’t fit a whole calendar in a small book bag.

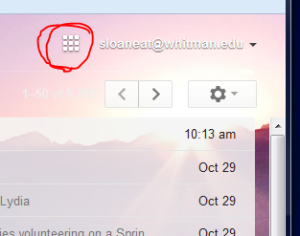

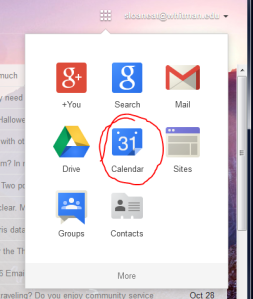

Google Calendar and Google Tasks are two great services that can be accessed from your Google Mail Page. To access Google Calendar simply click on the square icon in the top-right corner and then click on “Calendar”.

Having done this you will be greeted by a blank weekly calendar page. This page can be used for classes and studying times and whatever else you could think of. Like Google Keep, you can set reminders for events, by email or phone pop-up, and you can color code events.

Having done this you will be greeted by a blank weekly calendar page. This page can be used for classes and studying times and whatever else you could think of. Like Google Keep, you can set reminders for events, by email or phone pop-up, and you can color code events.

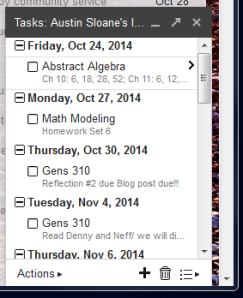

On the right of the above image you will notice the Google Tasks panel. To access Google Tasks, navigate back to the Google Mail page and click “Mail” in the top-left corner and then click “Tasks” and a small window will pop up on your Mail page and Calendar page.

On the right of the above image you will notice the Google Tasks panel. To access Google Tasks, navigate back to the Google Mail page and click “Mail” in the top-left corner and then click “Tasks” and a small window will pop up on your Mail page and Calendar page.

Google Tasks is a great way to keep track of assignments and their details. You can also organize your tasks by date or completely customize their ordering yourself.

Google Tasks is a great way to keep track of assignments and their details. You can also organize your tasks by date or completely customize their ordering yourself.

These are some of the tools I’ve come to become familiar with but this list is by no means exhaustive. As a college student, the main reasons these technological services found there way onto my list were because they were free and easy to set up! Also each technological service is paired with a more “dated” form, because I found both to be helpful. Technology is only as beneficial as it is useful, if one of these services has too much bloat then drop it immediately! (In favor of a paper strategy.)

Hopefully one of these ideas encourages you to better organize your work, good luck!

Works Cited

“Study Tip of the Week: Approach Your Material in Different Ways.” Web log post. ICM Blog RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Oct. 2014. <http://blog.icm.education/study-tip/study-tip-of-the-week-approach-your-materials-in-different-ways/>.

“Tooling and Studying: Effective Breaks.” MIT Center for Academic Excellence: Tooling and Studying. N.p., n.d. Web. 29 Oct. 2014. <http://web.mit.edu/uaap/learning/study/breaks.html>.